Reading time: 5 minutes

“I’m a storyteller and an observer. And I don’t want to pretend to be someone I’m not.” Mu Pan (Taichung City, 1976) is unequivocal. Visual tales are intrinsic to human experience, the places we go to discover new worlds and make sense of the one we live in. “If that’s illustration, then so be it,” says the Brooklyn-based artist, whose first museum retrospective, Mu Pan and Other Beasts, is showing at Espacio SOLO Madrid.

Visual narrative makes a comeback

Visual narrative, as Mu Pan’s comments indicate, continues to spark conflicting reactions. With the advent of abstraction in the 20th century, many avant garde artists rejected figuration and storytelling, while hugely influential art critics such as Clement Greenberg laid the academic foundations for viewing visual narrators as second-class artists.

In recent years, however, storytelling has been making a comeback. Figurative artists such as Pat Andrea or Neo Rauch are flourishing and prestigious institutions have re-visited narrative art through large-scale exhibitions including Storylines: Contemporary Art at the Guggenheim held at the Guggenheim, New York, in 2015. Our present-day context of social media, information overload and global interconnection is key to this resurgence of narrative. Through platforms such as Instagram, all of us are visual storytellers. Cultural mash-up is the norm and identities are fluid.

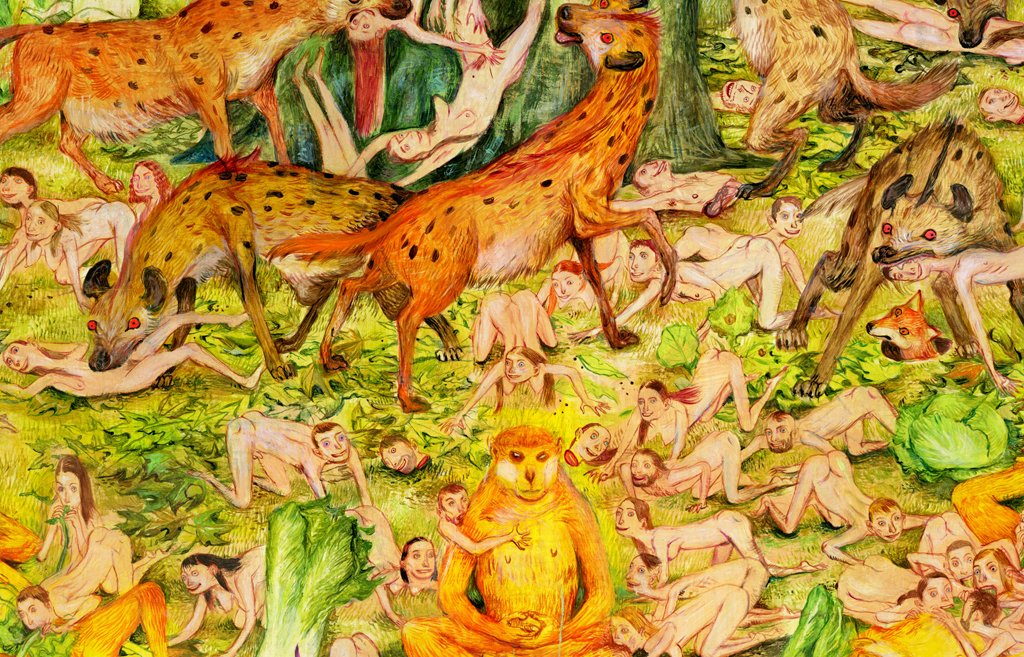

In this setting, Mu Pan’s artwork is particularly relevant. His large-scale acrylics, packed with action and detail, reflect the informative bombardment characteristic of our times and display an outstanding ability to blend disparate cultural references. Monkey armies battle to the death, superheroes are pitted against samurai, historical and cultural icons are cast into doubt. Classical Chinese literature, ukiyo-e and Indian miniatures, international relations and pop culture; Mu Pan fuses them all into brand new visual tales.

Observation and cultural mash-up

Mu Pan was born in Taichung City, Taiwan. He comes from a family of Chinese mainlanders, descendants of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces and refugees who fled to the island in the wake of the Chinese Civil War (1927-1949). The complex history of this region feeds directly into Mu Pan’s artwork: Japanese as well as Chinese cultural influences are clear. Samurai and tattooed yakuza, such as those depicted in Sharkuza: Shamurai (2018), are a recurring theme, while the artist’s approach to composition, line-work and detail draws on tradition of Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints.

In 1997, Mu Pan emigrated to the USA, where he studied and now teaches at the School of Visual Arts, New York. The artist’s personal background features in many of his works. Locusts (2015), for example, which depicts a family of monkeys eating together, recalls difficult childhood experiences. Mu Pan’s perspective as an immigrant to the USA, meanwhile, underpins artworks such as The Loyal Retainers Final Chapter: Battle Without Honor or Humanity (2018), which examines racism, class discrimination and the role of propaganda in popular culture.

A journey into Mu Pan’s universe

The exhibition Mu Pan and Other Beasts brings together over 20 major works by the artist, including the recently completed Mu Pan’s Garden of Earthly Delights (2019). An invitation to be thrilled by visual storytelling, this show is also the first retrospective organised by Colección SOLO. Free guided tours have been fully booked since opening, which has led SOLO to extend the exhibition, initially scheduled to run until the end of July 2019, through to the end of this year.

For this show, three large rooms at Espacio SOLO have been completely transformed to submerge visitors in Mu Pan’s unique world. In that world, however, Mu Pan is not alone: his art is presented alongside woodblock prints from Edo and Meiji period Japan, including works by ukiyo-e master, Utagawa Kuniyoshi.

The “floating world” of now

The city of Edo (1603-1867, now Tokyo) gave rise to an art form known as ukiyo-e, generally translated as “images of the floating world.” Woodblock prints of landscapes, kabuki actors, female beauties and even pornographic images were produced for a mass audience, gaining huge popularity. Outside Japan, ukiyo-e had a profound impact on the development of art in the West, directly influencing Monet, Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec, among many others. More recently, the linear aesthetics of ukiyo-e have fed into the super flat creations of Takashi Murakami and the development of manga and anime.

The term ukiyo is Buddhist in origin and referred to the suffering caused by the transient nature of life. By the 17th century, this meaning had been turned on its head. Instead of “suffering,” ukiyo meant “floating,” a glorification of the fleeting pleasures Buddhists had warned against. This concept of “the floating world,” of the exciting yet ephemeral, couldn’t be more relevant today. We live in the information age, a time when news — fake or otherwise — travels at the speed of light and fashions change from one Instagram post to the next. We are interconnected, overloaded, hyperactive: the floating world is now. Like Kuniyoshi in 19th century Edo, Mu Pan is a storyteller for his times.

It’s a monkey’s life

“I’m drawing because I’m bothered by everything around me,” explains the artist. “And the way I draw is like the way I try to escape. You feel so powerless, you try to find a way to create your own world, your own shelter to stay there and be isolated from the things that bother you.”

Human nature is his subject matter and monkeys his preferred visual substitute: “The only thing I keep doing is monkeys because that’s how I draw people.” In paintings such as White Boar and Watermelons (2015) the artist’s approach is naturalistic, while more recent works bring the monkey-human analogy closer through gesture and anatomies less rooted in the natural world.

Humour, linework and masterful gesture underpin Mu Pan’s creations. Animals grimace in pain, their bodies severed by lances or swords, while wolves or giant octopuses come to life at the stroke of a ballpoint pen. In the midst of conflict or in the depths of hell, we find yakuza-shark hybrids, beer-swilling primates and vegetables with legs. Mu Pan holds up a mirror to the present. If we dare to look, there’s a rabid monkey laughing back.

Plan your free guided visit to the exhibition here.